P12 Teachers' views on course analyses and the process at KTH

Teachers' views on course analyses and the process at KTH

“Where are all the course analyses and why are they there?”

Summary

Teachers at KTH are bound by national law and local regulations to perform course evaluations and course analyses and to make the findings and potential decisions available to the students by uploading them to the designated web portal. However, investigations of the data from this database show that few of the courses at KTH are represented herein. After interviews with teachers at KTH, there are strong indications that the faculty is in fact doing course analyses but not as stipulated. The teachers have adopted their own approaches that suit their individual situations. Analyzing the interview material using Vroom's expectancy-value theory, it is indicated that the teachers perceive the costs associated with following the stipulated process outweigh the benefits and that the values seen in performing course analyses are connected to their role as teachers.

Introduction

The work presented here is part of the KTH program “Future leaders for strategic educational development 2022” and certain elements of the project are, at the time of writing, still ongoing (e.g., the expansion of the interview material). Thus, the conclusions drawn here are based on the currently available data and the current framework used for the analyses.

An important part of constructive alignment [1] and the analyses of the individual courses and programs at KTH is the course analyses (CAs) that should be done “close in time” after the completion of each course. CAs exist as a means for the course-responsible teacher to, via the responses of the students, reflect upon the course in terms of the intended learning objectives, the different learning activities, and the results of the assessment tasks (formative and summative). The CA can be seen as a guide to evaluate the choices made during the course design but has in reality two distinct and different purposes; correction and development [2]. The correction serves as a quality assurance (QA) function (i.e., a potential “alarm bell”) where the CA aims to show what seems to work not so well (i.e., should be improved upon), what seems to work well (i.e., can be continued), that which has a large discrepancy between the intent of the teacher and the outcome (and should thus be drastically changed or removed from the activities) but also bring into light previously unknown issues. The development function of the CA can be done regardless of the state or "quality" of the course and serves as a quality enhancement (QE) function. Both from the view of the QA and the QE there are several things we can learn from the CA. It can, e.g., indicate if the learning activities are accurately coupled to the assessment tasks and the intended learning objectives. For example, a properly aligned assessment task with reliable and “good” examination results coupled with positive student responses hints at a course that is on the right track, whereas a course with "poor" results but with students enjoying it might indicate a course that fails to reach the intended learning objectives with the existing learning activities. A course with “satisfying” examination results but with very unfavorable responses could indicate a course that covers a topic that the students find to be interesting but the learning activities do little to create a good learning environment.

The CAs are therefore a fundamental instrument in evaluating the state of education at a university. Especially during times of significant change (e.g., the move to online teaching and more focus on digital tools) but also when new and important topics (e.g., sustainability or equality) are introduced throughout programs, the QA and QE functions of the CAs help teachers and program-responsible with correctly introducing new activities and new intended learning objectives. The measures taken, or required to be taken, for a course, based on the QA and QE are not necessarily the same. In addition, note that QA is inherently always required to be done after each course round (to assure that the quality of the course, for any reason, does not degrade). On the contrary, QE is, inherently, not needed after each course round if the course is already in a “good” state. It can even, convincingly, be argued that too frequent changes to a course will not give enough time for proper evaluation and reflection upon the changes made and could also leave students bewildered regarding the course design.

Background

The process, in place at KTH, to evaluate the quality of education does not merely rely on the CAs but they are an important part that is performed by the individual course-responsible teachers. The faculty at KTH is bound by The Higher Education Ordinance [3] which states (relevant phrases in bold):

”14 § Högskolan skall ge de studenter som deltar i eller har avslutat en kurs en möjlighet att framföra sina erfarenheter av och synpunkter på kursen genom en kursvärdering som anordnas av högskolan. Högskolan skall sammanställa kursvärderingarna samt informera om resultaten och eventuella beslut om åtgärder som föranleds av kursvärderingarna. Resultaten skall hållas tillgängliga för studenterna.”

Thus, KTH is bound by [3] to perform course evaluations, coalesce and reflect on the results and make this available to the affected students along with “any decisions about measures that are induced by the course evaluations”. The manuscript produced from this process is, here, seen as the CA of the course. Furthermore, at KTH the stipulated local regulations recommend how the CA should be performed, what items it should contain, etc. but also [4] that it should be made available through the stipulated web portal:

“Course analyses must be published on ”[...]” within one month after the final course meeting. The course analysis thus becomes available to students, teachers, Directors of First and Second Cycle Education, Directors of Third Cycle Education and Heads of School.”

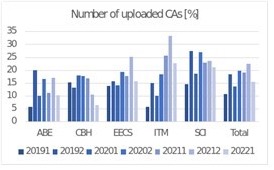

The KTH system containing the data for the uploaded CAs has the status for each course for a given semester (starting from spring 2019, e.g. [5]) and it paints a rather bleak figure. The number of CAs that are uploaded to the web portal is quite low, for example, for spring 2021, the upload rate (at the time of writing, Nov. 2022) is approximately 19% across all of the Schools at KTH (see below, left). To be fair, there are courses that span over two (or more) semesters which are then not easily represented but the historical data (see below, right) illustrate that this can’t alone explain the low number of uploaded CAs. It clearly hints at a, more or less, continuously low number of CAs being uploaded. The interesting research question to ask is why this is so.

| School | #courses | #CAs | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABE | 281 | 31 | 11 |

| CBH | 232 | 39 | 17 |

| EECS | 318 | 55 | 17 |

| ITM | 310 | 79 | 25 |

| SCI | 275 | 63 | 23 |

| Total | 1416 | 267 | 19 |

Methods of investigation

From observing the data above, we can state an initial hypothesis to potentially falsify: H1) “Many teachers don’t perform CA.”

This is a testable hypothesis. The speculation thus becomes if the teachers actually do the CAs, but don’t upload them, or if they don’t do them at all. The course analysis is perhaps seen as 1) pointless (“I know what will be said”, “I know what to change already”, “Everything is as good as it can be”, “The survey method used is not good/reliable.” etc.) or 2) uncomfortable (“I know that there will be problems and why”, “I don't want anybody to see what the students think of me/the course”, “This is my business and private” etc.). The unwillingness to perform CAs could thus perhaps be due to either disbelief in the process or due to underlying fear of being judged and found lacking in some aspect (i.e., the "imposter syndrome" [6],[7]). Thus, the overarching research question posed for the project is:

Q1) “How do KTH teachers view the stipulated process surrounding CAs?”.

The main tool for the data collection is interviews with teachers (both structured and impromptu interviews). The teachers were selected from the different schools of KTH (and thus being immersions in the different pedagogical sub-cultures at KTH) and also from a mix of the courses in the database over CAs [5] that has, or has not, a CA uploaded. The structured interviews started by centering on the teacher’s pedagogical background and general feelings concerning the stipulated process surrounding the CA at KTH and then, more focused, on specific aspects of the CAs to clarify the teacher’s viewpoints (following an interview structure as described in [8]). The interviews were then transcribed and coded for different themes or points. Two rounds of analyses were done on the material and both used concept-driven codes [8], i.e. codes developed in advance from selected existing literature and concepts.

First, an initial analysis was performed with the intent to potentially falsify H1 and to reveal what teachers see as expected benefits (B) and costs (C) [9] of doing CAs. Secondly, to better understand the motivations and choices teachers make when they are faced with the task of performing CAs, a different coding structure (other than simply “benefits” and “costs”) must be used. Thus, the material was coded for themes following Vroom's expectancy-value theory [9, 10, 11]. How and why individuals are motivated into different actions is a complicated phenomenon but the expectancy-value theory is based on the assumption that people act to avoid pain and experience enjoyment. A simplified version would say that:

Motivation = Expectancy • Instrumentality • Value

- "Expectancy" (E) [0:1], relates to an individual’s belief about their personal ability to perform a given activity at the perceived required level. It is the perceived relationship between the effort and the performance, e.g., “I believe I can run at this pace for the race”.

- "Instrumentality" (I) [0:1], relates to the individual’s belief about the probabilistic association between a performed activity and the wanted outcome. It is the perceived relationship between the performance and the outcome, e.g., “If I run at this pace during the race I think I can finish first”.

- "Value" (V) [-1:1], relates to the degree to which a reward is desired. It is the perceived relationship between the outcome and the reward, e.g., “I really want to win this race and get the prize.” This is further classified into:

- "Intrinsic value”, (iV), refers to the pure enjoyment felt when performing a task, e.g., “I really enjoy running.”

- “Attainmentvalue”, (aV), refers to the personal perceived importance of doing well on a task, e.g., “I think that one should be able to run well”.

- “Utilityvalue”, (uV), refers to the perception that a task will be useful for meeting future goals, e.g., “Being able to run well will keep me healthy.”

- “Cost”, (C), refers to that which the individual perceives compelled to give up, or endure, to be able to engage in a task or the effort needed to accomplish that task, e.g., “All the training and running takes time from my other hobbies.”

As can be seen, if any of the variables “E” or “I” receives a very low value (or zero) a person will have very low motivation to act, and if a person sees a negative "Value" in the action it is interpreted as trying to actively avoid performing the particular action. We can see that teachers will be highly motivated to do an activity if they 1) believe that they will be able to perform the activity as required, 2) that the successful performance of this activity will lead to a wanted outcome and that they 3) see a positive value in this outcome and not an overall cost. There are more complexities and details in the model than are presented here, but it is a good start for, e.g., mitigating obstacles and attempting to increase the incentives for doing CAs.

Results

So far, the findings of the interviews indicate that the hypothesis mentioned above, H1, can safely be discarded. I.e., teachers do indeed perform CAs and the reasons are often for both QA and QE measures. However, it is dominantly not as stipulated by [3] or the local regulations [4]. Teachers seem to have adopted individual approaches, some having similarities, that suit them and the particular course or situation well. The first analysis of the material investigated what teachers believe are the benefits and the costs associated with performing CAs:

Benefits:

- Tool to be able to develop the course and to find potential problems. I.e., being able to implement QE and QA.

- Clarity for the students so that they can follow the development of the course, what has been improved upon, how it works, etc.

- To reflect and develop as a teacher.

Costs:

- Time-consuming and messy with inflexible administration. A “Top-Down” management; too many "places"/web portals where things have to be uploaded. They are “bad templates” and “digital tools”. The students receive too many evaluations/surveys so they lose interest.

- Publicly available and open for the "world" leads to "green-washed"/self-sanitized CAs. “Academic suicide” and a feeling of being “graded” and “labeled” giving “dual” CA (i.e., one "real" and one “open”). Fear of students not choosing a course if it receives a “bad” result on the evaluation. Programs and courses losing students and KTH being slandered.

- No clear recipient, i.e., who reads and uses the CAs? “It is not meaningful work”.

- The data from the surveys are not credible or accurate in expressing the opinions of the students. In addition, the respondents may have an uncritical negative or positive image of a course.

From the second set of analysis, using expectancy-value theory, the observations are that the comments of the teachers indicate a:

Satisfactory expectancy (E). Low instrumentality (I).

No intrinsic value (iV) in the act of doing course analyses.

A clear attainment value (aV) with, what they perceive to be, accurately performed CAs.

A clear utility value (uV) following their individual approaches but not following the stipulated process.

Teachers interpret several large costs (C) associated with CAs; mainly in the form of waste of time and effort, as well as potential negative impacts to their academic careers, of doing CAs as stipulated.

In addition, throughout the interviews, it became clear that teachers do not place great trust in the current course evaluation surveys (i.e., the “Learning Experience Questionnaire (LEQ)”). In many cases, both course-responsible teachers and program-responsible teachers had other means of collecting, what they perceived to be, more accurate data. In most cases, this was done using different forums where the student body is involved (e.g., course boards /”kursnämnder”, meeting with the student unions, via “teachers teams” etc.).

Conclusions

It seems accurate to conclude that teachers at KTH do not approve of the stipulated process for CAs and they perceive costs of following it. However, teachers still see benefits with CAs and have adopted their own individual approaches to ascertain quality assurance and quality enhancement in their courses. From the analysis using expectance-value theory, it was further concluded that:

- The belief of the teachers is that they do have, what they perceive to be, the ability to perform CAs at the required level, thus, expectancy (E) is not a significant issue. This would hint at that actions, such as additional pedagogical training (in the topic of doing CAs) for the faculty, might not be the most effective measure in motivating the teachers to adopt a stipulated process.

- Secondly, the instrumentality (I) seems to be low, in part due to the teachers not placing trust in the data from the evaluation surveys. Thus, it indicates teachers not believing that their performance, following the stipulated process, will lead to the desired outcome (i.e., “better courses” via usable CAs with both QA and QE functions).

- The teachers believe that doing CAs (following their individual approaches) is useful (uV) but also that it is in their role as teachers at KTH to do CAs (aV).

Discussion

The internal processes and regulations of an organization can be complex and how this is affected by national law and how people inside the organization act is further still more complex. The work presented here should only be seen as a rough indicator of how the teachers at KTH perceive the processes surrounding course analyses and what motivates them in this regard. An important point, only briefly mentioned here, is the different academic subcultures that exist at KTH and how this reflects on the matter. It was thought that large discrepancies would be seen between, e.g., the different schools of KTH, but so far the views expressed by the teachers have been surprisingly homogenous.

References

[1]. J. Biggs and C. Tang; “Teaching for Quality Learning at University”, Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press, 2011.

[2]. K. Edström (2008); “Doing course evaluation as if learning matters most”, Higher Education Research & Development, 27:2, 95-106, DOI: 10.1080/07294360701805234

[3]. Högskoleförordning (1993:100) 1. Kap §14

[4]. https://intra.kth.se/utbildning/systemstod/om-kursen/kursens-utveckling/kursanalys-och-kursdata 1.1079678; accessible Nov. 2022

[5]. https://app.kth.se/kursinfoadmin/kurser/kurs/statistik/20191; accessible Nov. 2022

[6]. C. Brems et. Al.; “The Imposter Syndrome as Related to Teaching Evaluations and Advising Relationships of University Faculty Members”; Journal of Higher Education, Volume 65, Issue 2, 1994

[7]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Impostor_syndrome; accessible Nov. 2022

[8]. S. Brinkmann and S. Kvale; “Doing Interviews”, SAGE Publications Ltd, ISBN: 9781473912953

[9]. B. Studer and S. Knecht; “A benefit–cost framework of motivation for a specific activity”, Progress in Brain Research 229

[10]. V.H. Vroom and E.L Deci; ”Management and motivation”; Penguin 1970 [11]. V.H. Vroom; “Work and motivation”; Wiley, 1964